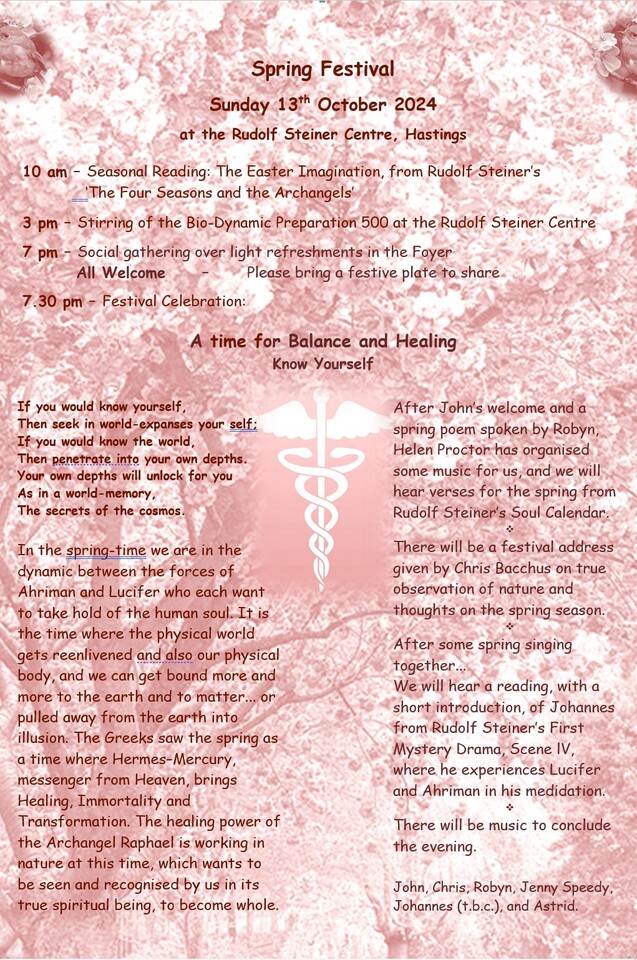

News 41: 13 OctoberAnthroposophy in Hawkes BayNewsletter 41-24 for Sunday 13 October 2024 Calendar of Coming Events-- Diary Dates In the Rudolf Steiner Centre, 401 Whitehead Road, Hastings

Contents:

--------------

Kathys' Therapeutic Pastel Class This term we carry on with 10 colour meditations from "The Green Snake and the Beautiful Lilly... We have some help from Peter Selge's book interpreting these mysterious pictures......Rudolf Steiner refers to Goethe’s fairy tale as "A new way to Christ" Where.....Rudolf Steiner Centre When...Wednesdays 10am - 1.30am Start 16th Oct Materials....Pastels and paper available from Humanity Cost ...$15.00 per class Contact....Kathy 027 233 0970. ---------------------------

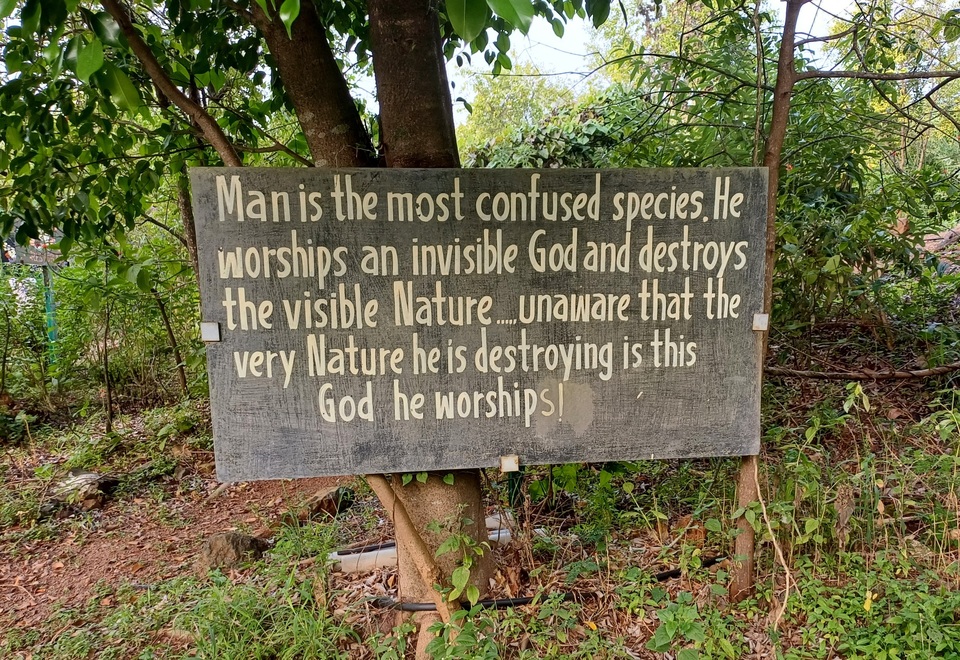

Foyer's Art Display Artist is Aileen Duckett Born and educated in Central Hawkes Bay, Aileen has been painting for seven years. Attending CHB College, she loved art but was unable to pursue it further as life and family took priority. Being a part of the andOtane Art and Crafts art group has given her confidence and purpose and her fellow painters are useful and friendly critics. ----------------------- Wagner's Libretto of Parsifal --- "The Grail and the Spear" , Thursday, 14th November at 7.00p.m. You are invited to the third talk/conversation/workshop on the topic of Wagner's Libretto of Parsifal. Together we will explore more of this marvelous "mystery drama" in particular the role of "the Grail" and "the Spear". The spear Parsifal returns to the Grail has the power to heal and redeem Amfortas. If possible, read the Libretto (again). I look forward to seeing all who are interested. ++ I am also hoping that some members will be interested - on a regular basis- to read and study Rudolf Steiner's explorations into the Spiritual Activity of Thinking. If you are interested in such a venture, please contact me. Eva Knausenberger 06-873 7615, or 021-2101859 or knausenberger2@gmail.com ----------------------- The First Seven Yearsby Erich Gabert The particular nature and the difficulty of the task of education in the first seven years, but the beauty and charm of it, too, is largely due to the fact that first of all the child is not receptive at all for reasonable considerations and warnings, and even later on, when it is approaching the seventh year, only very slightly so. It lives instead, however, in an almost limitless implicit confidence in the goodness, love and example of the grown-up, which very often is deeply shaming. Certainly the child is not conscious of this confidence; it grows out of the nature of its being in a completely elementary way, in basically the same way as the natural bodily processes of waking and sleeping, eating and drinking. Out of this confidence, which is based on the body and akin to nature, there arises, likewise, that very typical behaviour of the child, namely that it can and will not do otherwise than do what it sees the grown-up doing. That, for instance, (apart from abnormal cases) it cannot help but repeat the words or song that its mother speaks or sings to it. One calls this behaviour "imitation". However, it should never be overlooked that in order to be correct for the small child, the word sounds much too like conscious intention. Of course the child certainly can imitate intentionally too, sometimes amazingly well, but we do not mean that, here. We are referring to the quite unconscious taking-part in the life and the action of the grown-ups, whereby everything that they do in the presence of the child, or more exactly, what they are in the totality of their being is, as it were, sucked up by the totality of the child's being, right into the innermost stirrings of the child's being and will, but a will that still lies deep below the level of consciousness. We see a last remains of such unconscious participation when, as a grown-up, we see someone yawn and in that moment we yawn, too — not because we want to but because we have to. In this case the deepest layers of being are operating, the forces of life and habit that are at a still deeper level than the soul, where the more permanent traits of the human personality are rooted, the temperament, and that whole structure and texture of habits that is so characteristic for each human being. For this organism of habits, of formative life forces and processes, Rudolf Steiner used the old expression "etheric body". And it is just out of this world of bodily-etheric forces that the imitation of children actually arises. In this basic booklet "The Education of the Child from the point of view of Spiritual Science", that had appeared by 1907, Rudolf Steiner used a very instructive picture to show in what relationship this etheric organism of the child, in its first seven years, stands to that of the grown-up. He speaks about the etheric body of the child not being "born" until around the age of seven. This means that this whole world of the child's life forces and forces of habit is still as undivided from the same forces of the grown-up, forms together with them as unified and enclosed an organism as did the physical body of the child and the mother before physical birth. And just as at that time the blood circulation, nourishment etc. of mother and child interpenetrated in the most intimate way, so does the organism of the forces of bodily construction and of habits of the child still become permeated with those of the grown-ups living around him up to the seventh year (though of course not perceptibly to the senses). In order to indicate the fruitfulness of this thought-picture for education, especially moral education, may we begin with an example to show how, in a quite concrete case, action can be taken to prevent a painful result for the child, though it is not a moral punishment in the actual sense. Someone wants to protect a child that has just learnt to walk from burning its hands on the stove and learning that way to keep away from it. So, during the weeks before the stove was re-lighted a little game was played repeatedly with the child, in which a grown-up approached the stove with his hand but withdrew it in horrified haste without touching it. "Ouch, that is hot! We do not touch that!" The child copied it, repeatedly, until a healthy respect for the stove had developed into a natural habit. Now it was not necessary that it had to burn its hand in order to gain the required knowledge. The "punishment" could be dispensed with. Experiences of this kind, which anyone who has had to do with small children could certainly give many examples of, are instructive in various respects. Firstly, something like that must be done and not said. Exhortation achieves nothing, showing how to do it achieves everything. Further, it must all happen repeatedly, until it has become a firmly impressed habit. Both these qualities are inherent in play, and therefore with the right direction and guidance of play one really has one of the most powerful and magical pedagogical means at one’s disposal to work deeply into the inclinations and habits of the child. For a coddled child one can give the part in the game where it has to act forcefully, e.g. the smith, a timid child can be a lion, an unsocial child a mother who cares for her children. Along with the effort of living its way into the part and doing it as well as possible, forces are awakened that balance out the one-sidedness. Occasionally one will also be able to work with opposites. Just as one can, with a suitable toy, get a very slow child to become quicker and more awake, one can also help an unconcentrated and superficial child by giving him one toy after another too quickly, so that it longs, for once, to be left for a while with one thing. In each case one will work at the balancing of qualities and tendencies and will attempt, by so doing, to forestall the painful giving of offence to which one-sidedness can lead. Towards the end of this 7th year period, alongside the action in play-form, now the action in story-form, especially the fairy tale, becomes more and more important, although the effectiveness cannot appear fully until the next age group. For in the first seven years the strongest influence always arises out of what is actually done, not merely said. It is therefore good, when telling stories to children under seven years of age, to speak impressively as though modelling the scene, and to support the word in a variety of ways with lively, expressive gestures. For it is the gesture that impresses itself most deeply and works on most strongly. Just as the child assumes the gesture of speech, the quality of the voice and intonation of the grown-up, it also assumes the friendliness, the care, the eagerness to work, and the piety. But at this age it never stops with the external gesture, but what the hand or the whole body does is only the expression of what is being taken over likewise as inner soul attitude of friendliness, piety or joyfulness. This working into the body-building, habit-bearing forces of the child, into his etheric body can be very much reinforced by not only repeating frequently what one does with the children and what one lets them do, but by also bringing into this repetition a regular strictly-maintained rhythm. Things that are done in the same way each day, a fixed though not pedantic daily routine, regularity, and an ordered pattern in going to bed, all such things lay firm foundations for what will become effective in later life as deeply-engrained good habits, as the basis of character. It would be well, therefore, in the case of a little boy who is naturally greedy, to keep a special eye on good manners at table, on the washing of hands, on slow eating, on tidiness round the plate. One will also keep strict watch to see that the little fellow says "thank you" when he has received something, and that he gives others a share (though this will be done unwillingly at first.) None of this will be achieved by exhortations and commands but only by never omitting to set the example. It can often be helpful to say "Look, Mummy does it like this!" Then one can be certain that in that which has become habit one has achieved something that works on for life and which contributes strongly to the transforming of carelessness into firm will-power and instinctive egoism into consideration and love for one’s fellow men. The more one understands how deeply at this age pedagogical guidance penetrates into the being of the child, the more one will recognise how wrong the customary ideas often are. It is not the education of older children and young people that is the most important, most rewarding and most difficult, but the education of children of this tender age in particular. From the point of view of moral education the Kindergarten is much more important than the University. ------------------- One of a number of 'bon mot' from the "Hidden Oasis" Biodynamic retreat near Pune, India.

Posted: Sun 13 Oct 2024 |

| © Copyright 2025 Anthroposophy in Hawkes Bay | Site map | Website World - Website Builder NZ |